Recently, TreeBASE received the following request.

Hello!

I am just beginning to compile a submission.

The data-matrix is no problem. But in your introductory screens I see nothing explicit about the file format to be used for trees. By implication, these too should be in Nexus format, whereas I would prefer to submit tiff files of the actual published figures.

Please advise.

If you care about preservation, sharing, and reusability of phylogenetic data as much as I do, your first reaction might be that combination of annoyance and incredulity we typically refer to by three capital letters. And never mind that the submission instructions say "Data are uploaded to TreeBASE in the NEXUS format".

But upon closer inspection, as much as it appears like a case of data flirting1, it might just be a case of someone trying to save a beautiful tree. As Rob Guralnick, Mark Westneat, and I wrote in a submission to the 2012 iEvoBio Conference2:

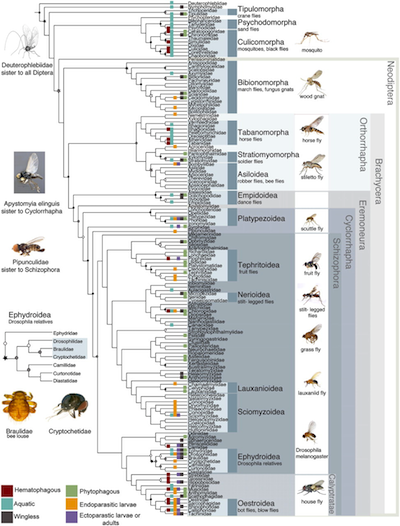

The story of biological evolution is highly complex and the subject of an enduring quest for better understanding. Yet it is also one of remarkable beauty, as given testimony by the numerous phylogenetic illustrations in publications that show in fascinating detail how traits, function, or morphology may have evolved along a tree. [Almost] all of them end up buried in articles, undiscoverable on their own, locked away behind paywalls, copyrighted by the publisher rather than the creator, and unavailable for repurposing.

Phylogenetic tree illustrations, such as the one to the right, can be rich in information much beyond the topology. Today, no good format exists for archiving this information, let alone in a machine-interpretable form3, other than archiving the image and archiving the accompanying (natural language) arcticle text. Text-based and thus machine-readable phylogenetic data formats such as NeXML4, NEXUS5, and Newick, to different degrees allow one to store metadata about elements of a tree right along with the tree, but at present even NeXML doesn't even come close4 to cover the whole breadth of visual adornments that authors might use to convey information. Hence, If one were to archive only the machine-readable version of a phylogeny, phylogenetic knowledge near and dear to an author's heart may easily be lost.

So why not archive both? Unfortunately, TreeBASE will not take an image of a tree, only a (text-based) NEXUS file. Or fortunately, depending on your perspective. At least it ensures that the phylogenies it holds are available in machine-readable form. The digital data archive Dryad shows that this otherwise isn't to be taken for granted. Although it gives some general guidelines, due to its broad disciplinary scope Dryad does not and arguably cannot impose strict requirements on the format of deposited data. This gives authors of published papers the flexibility to archive any kind of data they deem supporting the article or otherwise worth preserving. On the flip side this flexibility then doesn't prevent records which include a phylogeny only in image format. And looking at some examples (here and here), these don't even look like containing information in visual form that would be difficult or impossible to include in a text format.

Even a phylogeny that is archived in machine-readable format is not necessarily fit for a purpose that would require machine readability6. In response to the difficulties the Open Tree project has encountered7 in synthesizing a Tree of Life from all published trees, investigators from this and other large-scale phylogenetic knowledge synthesis projects are now drafting guidelines for how to archive a phylogeny so it can best be built upon by others in the future. Public comment and input is welcome, and will likely become part of phylogenetic data sharing mandates that NSF appears determined to include in funding opportunities8.

-

To my knowledge, the term data flirting was coined by Carole Goble, although it seems difficult to find a direct citation. I first heard her use it during her keynote at ISMB 2013, and it caught on instantly with the audience. The following is the best mention I could find on the interwebs, giving meaning and context:

"Papers are data flirting exercises", says .@CaroleAnneGoble - show some metadata to make people want the real thing. #ismbeccb #openscience

— Daniel Mietchen (@EvoMRI) July 23, 2013Here I'm extending the meaning of data flirting to include "show some non-reusable form of the data so I want to ask you for the real thing". ↩

-

Slides for the presented talk are on Slideshare. Interestingly, although it is a purely aspirational talk, in the sense that there is no active project or community initiative behind it (yet?), it is my second-most viewed slideshow on Slideshare. Perhaps it's the title that gets people to click on it accidentally? ↩

-

Efforts to address this have emerged. The Phylotastic II hackathon by NESCent's Hackathons, Interoperabiliy, Phylogenetics (HIP) Working Group gave rise to a subgroup named PhyloStyloTastic aiming to create a CSS-like standard for "styled" phylogenies. jsPhyloSVG is a JavaScript library that renders phyloXML-formatted phylogenies with graphical adornment markup.

See also this publication: Smits SA., Ouverney CC (2010) jsPhyloSVG: A Javascript Library for Visualizing Interactive and Vector-Based Phylogenetic Trees on the Web. PLoS ONE 5: e12267. ↩

-

Vos RA, Balhoff JP, Caravas JA, Holder MT, Lapp H, et al. (2012) NeXML: rich, extensible, and verifiable representation of comparative data and metadata. Syst Biol 61: 675–689.

One of the novelties of NeXML is that it allows arbitrary (RDFa-style) metadata annotation of any element of a phylogeny. In principle, this could include stylistic or graphical markup, but a convention or standard for such a markup annotation does not exist yet, let alone software that would interpret it. ↩↩

-

Maddison D, Swofford D, Maddison W (1997) NEXUS: an extensible file format for systematic information. Syst Biol 46: 590–621. ↩

-

This abstract, and the slides, for a lightning talk I and a group of collaborators presented at the 2013 iEvoBio Conference give some high-level background. See also this paper: Leebens-Mack J, Vision T, Brenner E, Bowers JE, Cannon S, et al. (2006) Taking the first steps towards a standard for reporting on phylogenies: Minimum Information About a Phylogenetic Analysis (MIAPA). OMICS 10: 231–237. ↩

-

Drew BT, Gazis R, Cabezas P, Swithers KS, Deng J, et al. (2013) Lost Branches on the Tree of Life. PLoS Biol 11: e1001636. ↩

-

Instead of the typically vague and generic statements found in past NSF program solicitations, recent ones have become increasingly specific (e.g., see the 2014 Dimensions of Biodiversity solicitation). Why these are problematic deserves its own discussion. I'll update this footnote with a link once that post is up. ↩

Comments

comments powered by Disqus